The Second Half of the Chessboard

There is a story loved by mathematicians, of an ancient emperor of India who was so pleased with one of his palace wise men, who had just invented the game of chess, that he offered this sage a reward of his own choosing. The sage, who was also a good mathematician, told his ruler that he would like just one grain of rice on the first square of his chess board, two grains on the second square, four on the third, and so on, doubling the number of grains of rice each time until all 64 squares of the chessboard had grains on them. This seemed to the emperor to be a very modest request, so he readily agreed, and called for his servants to bring some rice. He was surprised to find that the rice quickly covered the chess board, and then filled the entire palace. It soon became apparent that the emperor would be unable to keep his promise

In fact the first half of the chessboard would have to accommodate a heap of rice weighing 100,000 kilograms, but it is on the second half of the board that the amount of rice reaches astronomical proportions; literally, because if the rice grains on the whole board were placed end-to-end they would reach to the nearest star (Alpha Centauri) and back again. Piled up, the heap of rice would be larger than Mount Everest. On the 64th square of the chessboard alone there would be 263 = 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 grains of rice, more than two billion times as much as on the whole of the first half of the board.

To get back to aphids, parthenogenesis coupled with viviparity has given them the ability to double their population size is less than 3 days, given favourable conditions, so that starting from a single aphid, in about three months they would be beginning to populate the second half of the chessboard. In a year they would be nearing the end of their second chessboard, and we would not just be “knee-deep in aphids”, the whole world would be buried under a layer of aphids nearly 150 km thick (Harrington 1994).

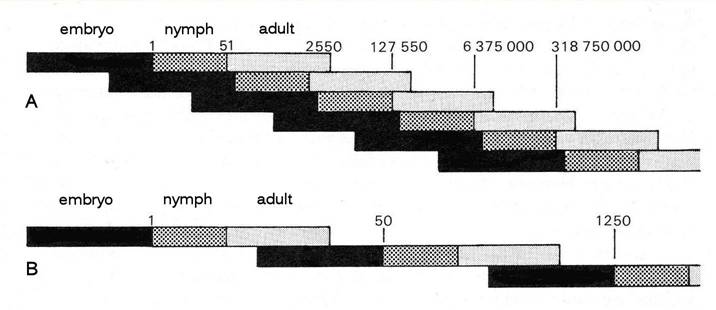

Let’s take a closer look at how aphids can reproduce so quickly, by using a diagram to illustrate the succession of generations in a parthenogenetic aphid, and compare it with that in an insect that reproduces sexually. The drastic effect of the telescoping of generations by the aphid can be clearly seen. We start with one egg of a parthenogenetically-reproducing aphid and one of the sexually-reproducing insect, suppose that both take exactly the same time to develop through embryonic and nymphal stages to adulthood, and also that both produce 50 progeny per female individual in each generation. In a short time the number of aphids is several orders of magnitude greater than the number of the sexually-reproducing insect. The difference between the two is further increased by the fact that, whereas all the aphids are females, we must assume that 50% of the individuals produced by the other insect are males, which make no contribution to its fecundity.

Fig. 1 Comparison of the powers of multiplication of A, an aphid reproducing parthenogenetically and B, a sexually-reproducing insect, assuming that both produce 50 offspring per female and that embryo, nymph and adult stages occupy the same period of time in each case. The figures show the potential number of descendants in successive generations starting from a single individual.

Of course, the comparison is not really as simple as this because the aphid is producing its young continuously, so that the generations rapidly start to overlap, whereas in most sexually reproducing insects the generations remain discrete, at least in temperate climates. It is this overlapping of generations that causes particular problems for the ecologists, in their attempts to explain how aphid populations do not rapidly escalate out of control, and bury the world in aphids.

Reference:

Harrington, R. (1994) Aphid layer. Antenna 18: 50-51.